Hidden Wonders of the Sahara: Celestial Glass, the Eye of the Desert, and Secret Waters

A meteor burst as hot as the sun, a billion-year-old magma structure and water, water everywhere

Ancient glass in the desert

The Sahara Desert holds many secrets, but few are as remarkable as the shimmering fragments of glass scattered across the Libyan Desert. These lumps of green and yellow glass, known as Libyan Desert Glass, have been collected and used for making jewellery for thousands of years.

The glass was not only prized for its unique beauty but also for the mystical allure of its cosmic origin. To the ancient Egyptians, the glass was a gift from the gods, a tangible connection between the earth and the stars.

The pieces range in size from tiny shards to chunks weighing over 20 kilograms (44 pounds). But why are there lumps of green glass just lying around in the desert.

Though the origins were unknown for millennia, scientists have recently determined that they were formed around 29 million years ago when a meteor exploded above the desert, unleashing intense heat rivalling the temperature of the sun. The molten sand rapidly cooled, forming translucent, yellow-green glass fragments scattered across the Libyan Desert.

The airburst generated extreme temperatures of over 3,000 degrees Celsius (about 5,400 degrees Fahrenheit), hot enough to melt the quartz-rich sand of the desert surface. Studies have identified the presence of lechatelierite, a high-silica mineral that only forms at such intense temperatures, confirming the glass’s origins from a high-energy impact event rather than volcanic activity or lightning strikes.

The glass also contains traces of rare elements, such as iridium, commonly found in extraterrestrial objects like meteors. These findings support the theory that the glass was created by a powerful meteor explosion above the surface in the atmosphere rather than a direct impact with the ground, since there is no large crater associated with the glass field.

The glass is found in the eastern part of the Sahara Desert, within the Libyan Desert region of Egypt, near the borders of Libya, Sudan, and Egypt, in the Great Sand Sea, a vast, remote, and arid expanse of sand dunes and rocky terrain. The glass field covers an area of about 6,500 square kilometers (2,510 square miles), making it one of the most significant occurrences of natural glass on Earth.

Libyan Desert Glass is not only a geological marvel but also a historical treasure that caught the eye of the ancient Egyptians who prized this otherworldly material for its beauty and rarity. Among the most famous artefacts made from this glass is a scarab-shaped amulet found in the tomb of the Pharaoh Tutankhamun. Set in gold, the amulet highlights the Egyptians' fascination with celestial objects and their symbolic connection to the gods. The scarab, a symbol of rebirth and protection, combined with the meteor glass, would have represented a powerful talisman that linked the wearer to the heavens.

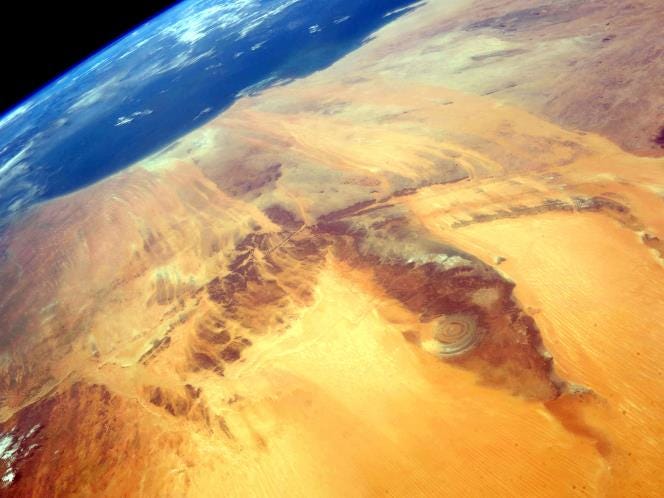

The Richat Structure: The Sahara’s Great Eye

The Richat Structure, often called the “Eye of the Sahara,” is one of the most striking natural features on Earth, a complex and extremely old geological formation in remote northwestern Mauritania. From space, it appears as a set of massive series of concentric ring shaped formations, spanning nearly 31 miles, or 50 kilometres, in diameter, resembling a giant bullseye or a human eye gazing up at the heavens.

This enigmatic feature was initially thought to be the result of a meteor impact due to its circular shape, but further studies have revealed that it is actually a deeply eroded dome of sedimentary rock, pushed up by volcanic intrusion from deep below the Earth's surface.

Concentric Ridges: The Richat Structure’s concentric ridges, layers of sedimentary rocks, including sandstone and limestone, that date back to the Proterozoic (around 2.5 billion to 541 million years ago) and the Lower Paleozoic eras (around 541 to 419 million years ago).

It’s a lot less impressive on the ground.

Over millions of years, wind and water erosion have stripped away the softer layers, exposing the underlying rings of resistant quartzite and dolomite, creating the structure's iconic appearance.

Dome Formation: The whole structure resembles a large dome formed from rock layers dating from the Late Proterozoic to the Ordovician periods, (around 1 billion to 444 million years ago) featuring three circular, outward-dipping ridges known as cuestas.

At its core, the Richat Structure has a shelf made of limestone and dolomite, surrounding a massive, fractured rock formation called a mega-breccia.

Intrusive Volcanic Rocks: The structure includes various volcanic intrusions, such as basaltic (gabbroic) ring dikes, kimberlitic intrusions (often associated with diamonds), and other alkaline volcanic rocks. The gabbroic ring dikes are believed to be connected to a large, deep-seated magmatic body, highlighting its origin from ancient volcanic processes.

Underground Watercourses and Aquifers of the Sahara

Deep beneath the seemingly lifeless and empty expanse of the Sahara’s sands lies a secret from the desert’s ancient past. The sand hides a hidden network of ancient rivers and vast aquifers criss-crosses the entire desert deep underground, popping back up to the surface to create the desert’s oases and deep wells. These underground water sources have sustained human settlements and wildlife since long before the Sahara became the arid desert we know today.

The most famous of these is the Nubian Sandstone Aquifer System, one of the world's largest fossil water reserves, which spans beneath several countries including Libya, Egypt, Sudan, and Chad. This aquifer holds water that is up to a million years old, preserved from a time when the Sahara was a much wetter region.

Another remarkable feature is the presence of "wadis," ancient riverbeds now dry on the surface but sometimes harboring hidden water flows beneath. These subterranean rivers occasionally reach the surface in the form of oases, creating pockets of life in the desert's harsh environment. The mysterious and vital role of these underground watercourses is a testament to the Sahara's dynamic and ever-changing landscape.