Mysteries of the Ancient Forests: Druid Symbols and Irish Fairy Forts, and How Trees Talk

The Druids' tree alphabet and Ireland's forbidden fairy forts

The Druid’s Tree Alphabet: Whisperings of the Ogham Stones

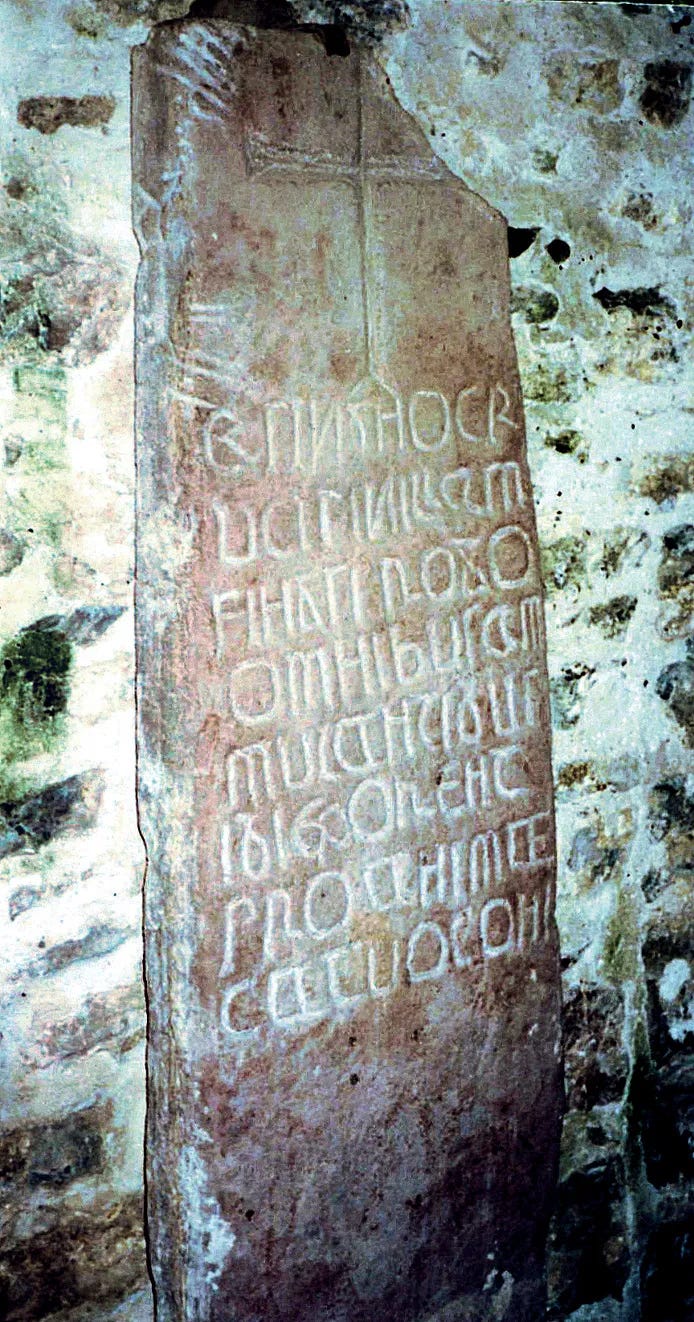

Imagine a world where every tree speaks its own language, each one a keeper of secrets whispered through leaves and branches. This is the world of the Ogham script, often called the Druid’s Tree Alphabet. Scholars think they date to around the 4th century AD, though this is disputed. Examples of this ancient writing system are found across Ireland’s rugged landscape and the Celtic corners of Wales and Scotland, carved not in books but along the edges of stones and wooden staffs, each stroke a message from the earth itself.

Ogham isn’t just an alphabet—it’s a living link between the Celts and the natural world. With twenty core characters, each one representing a different tree or plant, the script reads like a map of ancient knowledge. The first character, Beith, is for the birch tree, a symbol of renewal and fresh starts, while Duir, representing the mighty oak, stands for strength and endurance.

These mysterious marks are most often found etched into standing stones. But for the Druids, the meaning of Ogham likely went much deeper. Some believe it was a tool of magic and divination, a way for the Druids to encode their rituals and protect their sacred knowledge from prying eyes. And those prying eyes were mostly Roman.

Though the secrets of the Druids were kept strictly unwritten, some scholars suggest that Ogham may have been developed as a discreet or encoded form of communication among the Celts, potentially as a way to preserve their cultural and spiritual knowledge in the face of Roman pressure. When the Romans began invading the British Isles in the 1st century AD, Druids quickly became targets due to their powerful influence over Celtic society.

Roman accounts, often highlighting practices like human sacrifice, painted the Druids as dangerous and barbaric. By outlawing and persecuting the Druids, the Romans aimed to weaken Celtic culture and replace it with Roman customs, ensuring their dominance over the newly conquered territories. Starting after the establishment of Roman control, the use of Ogham on standing stones may reflect a need to assert and maintain Celtic identity secretly in a landscape dominated by Roman culture.

How trees communicate, heal and protect each other

Did you know trees can talk to each other? Hidden in the soil of the forest floor lies the “Wood Wide Web,” an incredible network where trees and plants communicate and collaborate through underground fungal connections. Known as mycorrhizal fungi, this system of filaments forms symbiotic relationships with plant roots, attaching themselves and spreading far into the soil to create an invisible web that creates biochemical links between countless trees and plants. Through this network, trees can share nutrients, send out chemical distress signals, and even help struggling neighbours, turning the forest into a dynamic, interconnected system of self-sustaining life.

When a tree is under attack by pests or experiencing environmental stress, it can release chemical signals through the fungal network to warn nearby trees, prompting them to bolster their own defenses. This system allows trees to share information about threats, such as insect infestations or drought conditions, and to coordinate their responses.

Additionally, the Wood Wide Web enables trees to share resources like water, nutrients, and carbon. Larger, healthier trees can transfer nutrients to smaller or struggling trees, helping to support the overall health and resilience of the forest. This underground exchange is particularly important in environments where resources are scarce, as it allows for a more balanced distribution of nutrients and enhances the survival chances of the whole forest community.

The mycorrhizal network also plays a crucial role in maintaining soil health, improving the uptake of essential minerals by plants, and even influencing plant growth patterns. This symbiotic relationship reveals a complex, interconnected ecosystem.

Don’t disturb the Irish fairy forts

Scattered across the Irish countryside, hidden among the green fields and misty hills, lie mysterious rings of earth and stone—these are the fairy forts, ancient relics that stir the imagination and whisper tales of a world just out of sight. Known locally as "ráth," "lios," or "dún," these circular structures are the remnants of ancient dwellings, ringforts, or early farmsteads, dating back to the Iron Age and early medieval period. But to the Irish, they are far more than just historical curiosities; they are portals to the Otherworld, sacred spaces guarded fiercely by the fairies, or "Aos Sí."

A renowned Irish folklore scholar tells a tale of a fairy encounter.

Fairy forts are typically small, circular enclosures surrounded by earthen banks, ditches, or stone walls, often overgrown with grass, wildflowers, or hawthorn trees, which are considered fairy trees. While archaeologists see them as defensive structures dating to Neolithic times, or simple farm enclosures for livestock, folklore paints a richer picture. These sites are believed to be the homes of the Sidhe, the fairy folk who inhabit the Otherworld—a realm parallel to our own, where time flows differently and magic is real.

To disturb a fairy fort is to risk invoking the wrath of the fairies, a prospect that still holds a potent sway over many Irish people. Stories abound of farmers who dared to plough through these ancient rings, only to be met with misfortune, illness, or even death. Construction projects have been diverted, roads rerouted, and trees spared the axe, all in deference to the unseen forces that are believed to dwell within these ancient circles. Even today, a surprising number of people in Ireland will avoid tampering with these sites, just in case the old tales hold true.

The forts are more than just physical remnants; they are living legends, connecting the past to the present through the power of story and belief. They embody a world where the mundane and the magical coexist, where history and myth blur into a landscape rich with wonder. To step into a fairy fort is to cross a threshold, to brush against the fringes of a world where the fairies dance, the hawthorn blooms, and the ancient ways are never quite forgotten.